By Abdul Tejan-Cole

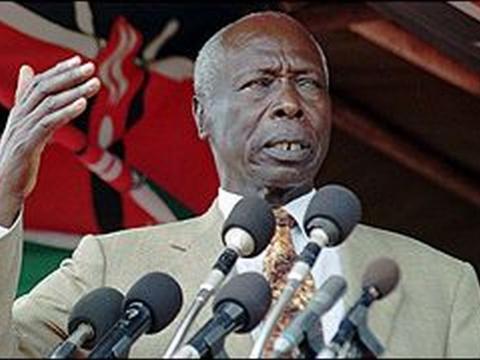

Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, the second and longest-serving President of Kenya, died on February 4 2020. After a period of national mourning during which the national flag was flown at half-mast throughout Kenya and its embassies abroad and his body laid in state at the parliament building in Nairobi for three days, he was given a state funeral with all civilian and full military honours. President Uhuru Kenyatta called him “a great son of Kenya, a cherished brother, a loving father, a mentor to many, a father of our nation, a champion of pan-Africanism."

Not all Kenyans agree with the praises showered by President Uhuru Kenyatta on Kenya’s most powerful man for the 24 years – 1978 to 2002 – when he reigned as President. To many objective analysts, his legacy was at best checkered, contested and controversial. Born in a small village of Kurieng’wo in Sacho Township of Baringo County about 270km north-west of Nairobi, even his date of birth was a source of contention.

Official records indicate he was born on September 2nd 1924, making him 95 at the time of his death. But according to his son, Raymond, quoted in the Kenya Daily Nation, “(W)e read in the magazines and newspapers that Mzee was 95 years old, but Mzee was not 95 and I think many of you have surmised that.” Raymond spoke of a friend of the former president who officiated at his wedding, Erik Barnett. “Mr. Barnett today is 103 years old. He and Mzee used to play football when they were young.” Raymond estimates that his dad was about 105 years old at the time of his death.

Born Toroitich arap Moi, he was born in relative poverty. Toroitich means “hug/embrace cattle” highlighting the importance of livestock to his Tugen subtribe of the Kalenjin ethnic group. Moi’s first career was as a herdsman. He may have remained one and may not have gone to school had he not been a very inept one. In his biography titled “Moi at 90”, written by his long-time press secretary, Lee Njiru, the story is told of how as a herdsman Moi spent three days on the road herding cattle and living off wild fruits. Moi never returned with the full herd of cattle. One or two were always missing. So when in the 1930s the missionaries asked parents to each give a boy to be enrolled in school, he was the natural choice for his family. Moi was shipped off to the Protestant Missionary Primary School. It was during his school days that he took the name, Daniel.

After finishing secondary school, he became a teacher and subsequently headmaster of the Kabarnet Intermediate School. In October 1955, Moi had his lucky break. Dr Joseph ole Tameno, the Rift Valley’s representative in the Legislative Council, had sobriety challenges and was deemed to be inefficient. He was forced to resign. A school inspector, Moses Mudavadi, whose son Wycliffe Musalia Mudavadi later served as Vice President under Moi, convinced Moi to leave his job as headmaster and run for the Legislative Council. On October 18, 1955, from a list of eight, Moi was chosen as one of the four African members of the Legislative Council. Later, Moi was part of the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) delegation that went to the Lancaster House Constitutional Conference of June 1960 which drafted the country's first post-independence constitution. In 1961, he was appointed Parliamentary Secretary in the Ministry for Education and later served as Minister of Education and Local Government.

Following Kenya’s independence, KADU was dissolved in 1964 and Moi rejoined the Kenya African National Union (KANU), then led by Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta. Moi was appointed Home Minister in 1964 and promoted to Vice-President in 1967. He served in this position until 22nd August 1978 when Jomo Kenyatta died of a heart attack following several strokes. That Moi succeeded Jomo Kenyatta was due mainly to Kenya’s long-standing Attorney General, Charles Njonjo. The elite Kikuyus, including the powerful Kiambu Mafia, did not want Moi to succeed Kenyatta and tried many stunts, including attempts to amend the constitution, all of which were thwarted by Njonjo. The conventional wisdom was that Njonjo helped Moi get the presidency because he felt Moi would be a weak president and it would be easy for him to take power from Moi.

As President, Moi’s key achievements included the introduction of the soon-to-be discarded 8-4-4 education system (eight years of primary education, four years of secondary, and four years of university education), free school milk programme, the expansion of universities, including private universities, major youth and women empowerment programs and the expansion of health, and general infrastructure development. The free school milk programme is said to have raised primary school enrolment by 23.3 per cent from 2,994,991 in 1978 to 3,698,216 in 1979.

But all of these achievements were overshadowed by the ruthlessness that prevailed during his tenure. In June 1982, Mzee Moi amended the constitution and made his party, KANU, the only legal party in Kenya. In response on August 1st 1982, a group of soldiers from the Kenya Air Force took over Eastleigh Air Base just outside Nairobi and captured the Voice of Kenya radio station in central Nairobi in an attempt to overthrow Moi’s government. The coup failed. All 2,100 members of the air force were arrested. It was estimated that more than 100 soldiers and close to 200 civilians, including Germans, an English, and a Japanese were killed in the aftermath of the coup. The Kenya Air Force was disbanded.

Moi’s reign of terror commenced. A statement by Amnesty International Kenya on the death of Moi stated: “Kenya under the 24-year-old presidency of Daniel arap Moi experienced some of the worst human rights abuses in its history… Acting in the public interest and dissent was dangerous in the eighties.” Moi was accused of organising assassinations of opponents. The Amnesty statement refers to the assassination of Robert Ouko, who served as Foreign Minister of Kenya from 1979 to 1983 and from 1988 to 1990. His mutilated remains were found by a herds boy about 2.8km from his Koru farm. He had been shot, his body had been partially burnt; there was virtually no face remaining, so he had to be buried with a facemask. His murder remains unsolved to date. Outspoken Anglican Bishop Alexander Muge died in a mysterious road accident on August 14, 1990. A former intelligence officer told the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission that security agents killed Muge and the accident was a cover-up. There were many others.

Ruthlessness came easily to Moi. His opponents were locked up in underground torture chambers and others murdered. The Wagalla massacre described as “the worst human rights violation in Kenya's history” happened during his tenure. About 5,000 Kenyan-Somalis were taken to an airstrip, prevented from accessing food and water for five days before being executed in February 1984. The Kenyan government put the official number of dead at 57. The Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission stated in its report that "close to a thousand" people were killed in Wagalla. The Commission also stated it was "unable to determine the precise number of persons murdered". It concluded that security agents committed other atrocities including "torture, brutal beatings, rape and sexual violence", as well as "burning of houses and looting of property."

In an article following his demise, Makau Mutua, Chairman of the Kenya Human Rights Commission opined that “This is how Moi’s epitaph should read: ‘Here lies the dictator who looted Kenya dry, completely impoverished it, and committed gross and grave human rights violations’…Moi’s name will forever be printed in the sands of time along with his fellow dictators – Zaire’s Mobutu Sese Seko, Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, Chile’s Augusto Pinochet, Philippine’s Ferdinand Marcos, Somalia’s Siad Barre, Ethiopia’s Mengistu Haile Mariam, and Romania’s Nicolai Ceausescu. Those will undoubtedly be his roommates in the afterlife.”

Moi was also a rabid tribalist. He persecuted ethnic groups linked to the opposition and gave the best jobs to those from his Kalenjin tribe. During his tenure, the economy stagnated, the press was muzzled and an atmosphere of fear of oppression was never far away. Major scandals of misappropriation of government funds were always hushed up. Ministers, politicians and senior civil servants seized public land and deprived thousands of poor agrarian people of their livelihoods. Transparency International estimates that over US$ 3 billion was stashed abroad by Moi and his close associates. Under Moi, Kenya fell deeper into economic stagnation, with low or negative growth and periods of steep inflation.

Moi got away with repression and corruption by siding with the West during the Cold War. At the end of that war he was pressured to restore multi-party democracy. This was done in 1991. He “won” the 1992 and 1997 elections largely because the opposition failed to unite behind a single candidate. Having served two terms following the restoration of democracy, Moi shocked his opponents when he agreed to step down in 2002. He chose and endorsed the current president and son of Jomo Kenyatta, Uhuru Kenyatta, as the KANU candidate for the presidency. Uhuru lost the election to a united opposition, the rainbow coalition led by Mwai Kibaki. Following this defeat, Moi retired from active politics.

Mzee Moi’s legacy is heavily contested in Kenya. Moi Day was scrapped as a holiday in 2010 only to be reinstated by the courts in 2017. Although the brutality and terror he dispensed is not so much prevalent today, the tribalism, corruption, nepotism that he perpetuated laid the foundation for the ethnic conflicts of 2007/8 and many of the country’s present problems. Most of the current politicians served in his government and continue to espouse his beliefs. One of the strong contenders to replace Uhuru Kenyatta is Moi’s youngest son, Gideon, who is currently the Chair of KANU. If he succeeds the baton will once more be exchanged between the Moi and Kenyatta dynasties and political power in Kenya will continue to reside with Mount Kenya, Nyanza and Rift Valley families.

Copyright (c) 2020 Politico Online