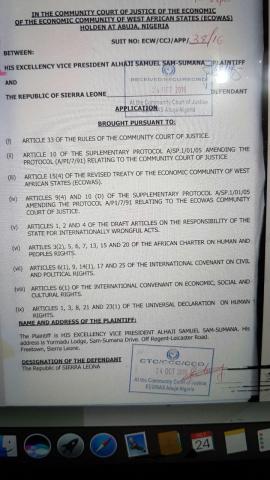

Application at the ECOWAS court

SUBJECT MATTER OF PROCEEDINGS:

a. Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Protection and Security of the Law as enshrined in Article 3(2) of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights.

b. Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Due Process of the Law as enshrined in Article 7(1) of the African Charter on Human and People’ Rights and Article 14(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

c. Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Work as enshrined under Article 15 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Article 23(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and Article 6(1) of The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

d. Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Participate in Government as enshrined under Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Article 13 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights; and Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

e. Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Personal Safety and Security as enshrined under Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Article 6 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights; and Article 9(1) of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights.

f. Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Dignity under Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 5 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and Article 1 of Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

FACTS:

WHEREAS:

i. The Republic of Sierra Leone is a signatory to the revised Treaty Establishing the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) dated 24th July, 1993.

ii. The Plaintiff is a Community Citizen within the meaning of Article 1(1) (a) of the Protocol A/P3/5/82 relating to the definition of the Community Citizen.

iii. The ECOWAS Treaty, the ECOWAS Court Rules of Procedure, the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the Body of Law as contained in Article 38 of the Statutes of the International Court of Justice, are all applicable by this Court to this case by virtue of Article 19 of the Protocol on the Community Court of Justice.

iv. The actions taken by the President of the Republic of Sierra Leone, the purported Vice President, and the Supreme Court of the Republic of Sierra Leone are directly attributable to the Republic of Sierra Leone by virtue of the Draft Articles on the Responsibility of the State for Internationally Wrongful Acts; and it is provided under Article 2 of the Draft Articles that there is an internationally wrongful act of a State when conduct consisting of an action or omission: (a) is attributable to the State under international law; and (b) constitutes a breach of an international obligation of the State; and under Article 4(1), the conduct of any State organ shall be considered an act of that State under international law, whether the organ exercises legislative, executive, judicial or any other functions, whatever position it holds in the organization of the State, and whatever its character as an organ of the central Government or of a territorial unit of the State; and Article 4(2) continues on to state that an organ includes any person or entity which has that status in accordance with the internal law of the State; and Article 4 recognizes the President of the Republic, the purported Vice President, and the Supreme Court of the Republic as organs of the State.

v. The failure of Sierra Leone to provide an effective remedy for the violation of the rights of the Applicant has necessitated the Applicant’s resort to the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice.

vi. This Court held emphatically in the case of Obioma C.O. Ogukwe v Republic of Ghana ECW/CCJ/APP/12/14 [Appendix 63] that States will be held responsible if they fail to act with due diligence to prevent violations of the rights, or to investigate and punish acts of violence and for providing adequate compensation. The Republic of Sierra Leone, therefore, had a responsibility to first prevent, and upon the violation of the Applicant’s rights, to provide effective remedies for the violations.

vii. Failure to provide such effective remedies means that the State is in default of Article 7 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights and Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Such was the principle espoused by this Court in Sidi Amar Ibrahim and Another v. The Republic of Niger ECW/CCJ/JUD/02/11. In Abia Azali and Another v. Republic of Benin ECW/CCJ/JUD/01/15 [Appendix 55], in criticising the failure of Benin to take appropriate action to ensure the rights of the Applicant, this Court took the view that “the situation is indicative of the undisputable negligence on the part of the judicial services, coupled with signs of a malfunctioning judicial machinery, all continuing to jeopardise the rights of applicants. The inertia of the judicial authorities has led to an objective situation of denial of the rights of the victims.” In short, States are to be held responsible if they fail to act with due diligence to prevent violations of rights or to investigate and punish acts of violence and for failing to provide adequate compensation (see African Commission in Amnesty International and Others v Sudan (2000) AHRLR 297 [Appendix 56] and in Malawi African Association and Others v Mauritania (2000) AHRLR 149 at 164-165 [Appendix 57]).

viii. The ECOWAS Court is empowered to hear cases in which domestic courts had given judgments. Once human rights abuse can be established, the ECOWAS Court is competent to exercise its jurisdiction over the matter, as in Mrs. Ameganyi Manavi & Ors v The Republic of Togo (2011) CCJELR 35, where the applicants were Parliamentarians in Togo. Owing to internal crisis in their political party, Union des Forces du Changement (UFC) a new political party was formed. In order to remove them from the Parliament, a letter from the chairman of the UFC addressed to the President of the National Assembly claimed that the Applicants had transmitted letters of resignation to him, supposedly emanating from the Applicants. On the basis of the falsified letters the Constitutional Court of Togo certified that the seats of the applicants had become vacant. In a suit filed at the ECOWAS Court, the Applicants alleged that their human rights were violated and they cited the ECOWAS Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance, the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Constitution of Togo. The preliminary objection of the defendant that the matter had been determined by the Constitutional Court of Togo was dismissed by the ECOWAS Court. Having found that the purported letters of resignation were forged, the ECOWAS Court ordered the reinstatement of the Applicants as Parliamentarians.

NARRATION OF FACTS BY THE APPLICANT:

a. The Applicant was duly elected Vice President of the Republic of Sierra Leone in August 2007 and again in September 2012. He stood and was elected as a candidate of the All People’s Congress Party (herein referred to as “APC Party”) and both times as the running-mate of Dr. Ernest Bai Koroma. This was done pursuant to Section 54 of the Constitution of Sierra Leone (herein called “the 1991 Constitution”) [Appendix 1], Article 6.9.3 (iii) (g) of the Constitution of the APC Party [Appendix 2], and Section 45 of the Public Elections Act, 2010 (Act No. 4 of 2010) [Appendix 50].

b. On 10th March 2015, the Applicant, whilst serving as Vice-President, received a letter dated 6th March 2015 from the APC Party’s National Secretary General, [Appendix 3] expelling him from the Party upon the purported approval of the Party’s National Advisory Council with effect from Friday, 6th March 2015, purportedly in accordance with Article 8 of the Party’s Constitution.

c. The letter alleged that a complaint had been submitted to the Chairman and Leader of the APC by one Karoma Kabba, whose integrity has since come into question [See Appendix 12]. The letter of complaint does not provide details of the allegations made against the Applicant. The letter chronicles a sequence of events in which the Applicant was invited to appear before an Investigation Committee constituted by the National Advisory Committee (NAC). It further states that the Applicant appeared before the Investigation Committee and gave his reaction to that Committee, and that the Committee allegedly submitted some findings to the NAC, which purported to endorse those findings [See Appendix 3].

d. The National Secretary General of the APC Party further stated in his letter to the Applicant that, based on the findings of the Investigation Committee, the Applicant had been dismissed as a member of the Party on grounds of behavior amounting to fraud, inciting hate, threatening the personal security of key party officials, carrying out anti-party propaganda, and engaging in activities inconsistent with the Party’s objectives. There were no further elaborations in the one-page letter, as to which particular actions of the Applicant amounted to the alleged grounds for his dismissal [See Appendix 3].

e. On 14th March 2015, the Applicant was forced to flee his home with his wife, fearing for his life, after soldiers surrounded his house and disarmed his security team. All thirty-eight (38) officers in his security detail were removed and five unknown armed men took their place, prompting the Applicant to put in a call through to the United States Ambassador to Sierra Leone to convey that his house was under attack. The Sierra Leone Government however claimed that the Applicant was not in any danger and that the soldiers only came to his house to rotate his security team.

f. In a Press Release dated 17th March 2015 [See Appendix 6], a mere 11 days after his purported dismissal from the APC Party, the Applicant heard it announced on National Radio and Television that the Republic “had relieved him of his duties and office as Vice President of Sierra Leone” by reason that the Applicant was “no longer a member of a political party in Sierra Leone” and therefore did not have “the continuous requirement to hold office as Vice President of the Republic Provided for in section 41(b) of the 1991 Constitution” and because the Applicant “sought protection from a foreign Embassy.” The Applicant did not personally receive any official communication to that effect, but later obtained a copy of the said Press Release [See paragraph 1 of Appendix 8; see also Appendix 6].

g. In answer to the State House Press Release, the Applicant issued a Press Release on the 18th March 2015 [Appendix 8] in which he contended that the President had no power to “relieve him of the duties and office of Vice-President”, especially so far as the 1991 Constitution makes provision in its Section 55 for the circumstances in which the Office of Vice-President could become vacant, particularly at Section 55(c). The Applicant contended in his Press Release that his purported removal from the office of Vice- President was both “unconstitutional and unlawful.” The Applicant also took steps to address his political supporters and well-wishers, advising that they “remain calm” and “abide by the law always.”

h. On 19th March, 2015, the President purported to appoint Mr. Bockarie Foh as Vice-President of Sierra Leone, purporting to have acted under Section 54(5) of the 1991 Constitution [See Appendix 9]. Mr. Bockarie Foh has since purported to assume the Office of Vice-President of the Republic of Sierra Leone.

i. On 20th March 2015, the Applicant, through his solicitors, invoked the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone, being the country’s constitutional and highest Court as well as final Court of Appeal locally, by means of an Originating Summons for a determination of the constitutionality of the President’s actions against him [Appendix 10].

j. Whilst the said Originating Summons was pending, the Applicant filed a Motion dated 24th March 2015 seeking an interlocutory injunction against Mr. Victor Bockarie Foh, the impugned Vice-President, to restrain him from continuing to hold the Office of Vice-President pending the determination of the Originating Summons [Appendix 11].

k. In further response to his sudden expulsion from the APC and the unfounded and dubious reasons for same, the Applicant invoked his right of appeal under article 8(i) of the Party’s Constitution by serving an Appeal against his expulsion by the letter signed under the hand of the Party’s National Secretary General and dated 26th March 2015 [Appendix 7]. The Applicant has since neither been informed of any proceedings relating to his Appeal nor was he called upon to participate in any appellate hearing or other proceedings.

l. On 8th April 2015, the Applicant filed a Supplemental Affidavit to his Originating Motion [Appendix 33] exhibiting inter alia, the APC Party’s Expulsion Letter, his Appeal against same and a copy of the APC Party’s Constitution. On the same date, 8th April 2015, the Attorney-General, filed their Statement of Case [Appendix 34]. On 20th April 2015, the purported Vice President also filed his Statement of Case in the Supreme Court [Appendix 35].

m. The Supreme Court Justices, on 5th May 2015, delivered their individual but unanimous Rulings dismissing the Applicant’s Application for an injunction, inter alia, on the basis that the balance of convenience was in favour of dismissing the application, and that the Applicant had failed to adduce adequate evidence in support of his application for injunctive relief [Appendix 37].

n. On 15th May 2015, when hearing commenced on the Applicant’s Originating Motion, the Defendant objected to the Applicant’s Counsel’s reference to and use of Applicant’s Supplemental Affidavit, on the ground that the Applicant had not served him with the Supplemental Affidavit, even though it was already part of the Court’s records. On the same day, the Court made an Order for the Defendant’s Counsel to be served with the Supplemental Affidavit of the Applicant and granted the Defendant leave to amend its Case Statement accordingly. This Order of the Supreme Court was, however, erroneously dated 15th December, 2014 [Appendix 37].

o.Without complying with the Supreme Court’s Order to possibly amend his Case Statement, the Defendant filed a Notice of Motion dated 19th May 2015 [Appendix 38] inter alia requesting the Court to set aside its Order of 15th May, 2015 as being irregularly made, considering, according to Counsel, that the Applicant had not applied to amend his Case Statement before filing the Supplemental Affidavit aforesaid.

p. On the 1st of June 2015, upon hearing the Defendant’s Notice of Motion, the Court amended its 15th May 2015 Order by inter alia ordering further that the Supplemental Affidavit aforesaid be served on the Defendant; that the Applicant, if he so desired, amends, files and serves his Case Statement on the Court and the Defendant by 4th June 2015, failing which the Supplemental Affidavit shall not be used in the proceedings. The Court further ordered that the Defendant may also amend its Case Statement upon service on it of the Applicant’s amended Case Statement, not later than 9th June, 2015 [Appendix 39].

q. On 4th June 2015, in a bizarre development, the Applicant’s Solicitor and Counsel, Messrs. Jenkins- Johnston & Co., contrary to the instructions of the Applicant, their client, and without consulting him, filed a Notice to the Court of their intention not to amend the Applicant’s Case as ordered by the Supreme Court [Appendix 43].

r. On the 8th of June 2015, the Applicant’s Solicitor and Counsel had as yet not amended and filed the Applicant’s Case Statement in order to reflect the contents of the Supplemental Affidavit and so the Applicant was constrained to terminate their services and to replace them with Messrs. CF Margai & Associates, working together with Mohamed Pa-Momo Fofanah Esq. [See Appendix 41].

s. On 10th June 2015, Messrs. CF Margai & Associates filed a Notice of Motion to the Court seeking inter alia, an Order to extend time within which the Applicant can file his amended Case Statement as well as an Order to expunge the Applicant’s erstwhile Solicitors’ Notice to the Court, in which he had refused to amend the Applicant’s Case [Appendix 42]. The Defendant opposed the Application.

t. The Ruling of the Court delivered on 15th July 2015 [Appendix 44] refused the Applicant’s Application, holding inter alia that his erstwhile Counsel and Solicitors had “sufficient authority to file and serve the said Notice” and that the Notice was “neither scandalous, nor irrelevant or oppressive”; therefore, the Court could not expunge it as requested.

u. The Court subsequently proceeded to hear and determine the entire Matter by hearing arguments and submissions from the respective Counsel of the Parties concerned. The Court then handed down its Final Judgment on 9th September 2015 and the five Justices in their respective individual Judgments unanimously refused all of the declarations sought by the Applicant in his Originating Motion dated 20th March 2015 [Appendix 45].

v. The Applicant, consequently, has exhausted all local remedies available to him under the Laws of Sierra Leone, considering that the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone is the constitutional and final court of appeal in that country. Furthermore, the Applicant contends that the Supreme Court’s Ruling of 15th July 2015 and the Final Judgment delivered on 9th September 2015 condoned the various rights violations he had suffered, and itself violated his fundamental and constitutional rights regarding due process of law; protection and security of the law; right to work; right to participate in governance; right to personal security; and right to dignity, as elucidated below, thereby necessitating the intervention of the ECOWAS Court.

HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY THE DEFENDANTS AGAINST THE APPLICANT

(1) Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Protection and Security of the law

1. The Applicant’s Right to Protection and Security of the Law were violated in the following five (5) Respects:

a. The Applicant was expelled from the APC Party without regard to Article 8(ii) of the APC’s Constitution [Appendix 3] which empowers the Party’s Executive Committee, not the National Advisory Committee, to decide on disciplinary measures against a Member.

b. The Applicant was removed from the Office of Vice President and was purportedly replaced with Mr. Bockarie Foh without regard to Sections 54, 55, 50, and 51 of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone which provide for the manner by which the Vice Presidency becomes vacant [Appendix 1].

c. The President purported to replace the Applicant with Mr. Bockarie Foh through a misapplication of Section 54(5) of the 1991 Constitution.

d. The Supreme Court of Sierra Leone denied the Applicant the opportunity to fully and exhaustively present his case to the Court, without regard to sections 15(a), 23(2) and 28 of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone [Appendix 1] and rule 93 of the Supreme Court Rules [Appendix 49].

e. The Supreme Court of Sierra Leone failed to correctly apply the provisions of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone, and erroneously held that the Applicant had lost a constitutional criteria required to maintain his Office as Vice President and that the President had the authority to remove the Applicant from office, without regard to sections 54, 55, 50, and 51 of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone [Appendix 1].

2. The right to Protection and Security of the Law is enshrined in Article 3(2) of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights [Appendix 16], which provides that all persons shall have equal protection of the law.

(1.1.)1. Expulsion from All People’s Congress Party without regard to Procedure in Party Constitution

3. It is the Applicant’s submission that where individuals have been provided certain rights or privileges by law, it is only through lawful means that those rights or privileges may be curtailed. The Applicant, as a member of the APC Party is entitled to the guarantees of membership as captured under the 1995 Constitution of the APC Party.

4. The expulsion of the Applicant from the APC Party, however, violated his right to the protection and security of law because the body that purported to expel him, the NAC, acted outside of its mandate under the 1995 APC Party Constitution. It is provided for under article 8(ii) of the 1995 APC Party Constitution [Appendix 2] that disciplinary measures which are taken against members of the APC Party must begin with a decision from the Party’s Executive Committee. After the said decision of the Executive Committee is made, the NAC is then to be notified and presented with records of the actions of the Executive Committee. [See article 8 (iii-v) of Appendix 2].

5. The procedure as laid out above, is the lawful process which the Applicant should have been subjected to. The Party Constitution provides a capable decision making body and strict procedures which should have been followed.

6. This Court is referred to the case of Good v Botswana (2010) AHRLR 43 (ACHPR 2010) [Appendix 20]. At paragraph 170 the Court stated that, “The right to be heard requires that the complainant has unfettered access to a tribunal of competent jurisdiction to hear his case. It also requires that the matter be brought before a tribunal with the competent jurisdiction to hear the case. A tribunal which is competent in law to hear a case has been given that power by law: it has jurisdiction over the subject matter and the person. Where authorities put obstacles on the way which prevent victims from accessing the competent tribunals or which oust the jurisdiction of judicial organs to hear alleged violations of human rights, they would be denying victims of human rights violations the right to have their causes heard.”

7. The Applicant submits that he was never summoned by any Executive Committee of the Party to a disciplinary hearing in respect of the allegations made against him. Instead, the NAC of the APC Party invited the Applicant to appear before an Investigation Committee which it had unlawfully constituted [See Appendices 3 and 7].

8. The decision to remove the Applicant from the APC Party was made in excess of the powers granted to the NAC. It was made contrary to clear provisions assigning the decision making authority to the Executive Committee; and was therefore, within the circumstances, an infringement on the protection which is afforded him under the 1995 APC Constitution.

(1.2) Removal from office of Vice President by the President, contrary to provisions in 1991 Constitution

9. Much like the National Advisory Committee, the President lacks the competence at law to remove the Applicant from his position as Vice President of the Republic of Sierra Leone. Therefore, purporting to remove the Applicant from his position either in reliance on the decision of the NAC or on the grounds that the Applicant lacked “the continuous requirement to hold office as Vice President of the Republic Provided for in section 41(b) of the 1991 Constitution...”, or on the allegation that the Applicant had exhibited “a willingness to abandon his duties and office as Vice-President” [Appendix 6] deprived the Applicant of the opportunity to appear before the competent body which the Constitution has mandated to determine whether or not a Vice-President should be removed from office.

10. This Court is again referred to the emphasis which was laid on the requirement of a competent court or tribunal in the case of Good v Botswana [Appendix 20]. At paragraph 170 it is clearly stated that where, “A tribunal which is competent in law to hear a case has been given that power by law: it has jurisdiction over the subject matter and the person.” The provisions of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone provide for the appropriate bodies which are to decide on whether or not the Vice President should be removed from office [see Sections 50 and 51 of Appendix 1] and nowhere is it stated that the President has been vested with such authority.

11. Justice Dr. Abdulai Conteh, a former Chief Justice of the Belize Supreme Court and Justice of the Court of Appeal of the Cayman Islands, wrote an open letter to the President dated 18th March 2015, as a concerned citizen of Sierra Leone and in his capacity as a Justice of the Court of Appeal of the Commonwealth of the Bahamas [see Appendix 14] to express to the President that he lacked the constitutional capacity to remove the Applicant from his office as Vice President. Justice Conteh is also a former minister from Siaka Stevens’ APC Government (1977-1984); and also served, significantly, as Attorney-General and Minister of Justice (1987-1991); and again significantly, as First Vice President and Minister of Rural Development (1991-1992).

12. In his letter, the learned Justice competently explained why the actions of the President were well above the powers which the Constitution granted him. The learned Justice referred to Section 54(1), (2), and (3) of the 1991 Constitution and noted that a candidate for President must have a running mate designated as Vice President. Together, if successful, they are declared President and Vice President respectively. The learned Justice distinguished the 1991 Constitution from those of 1971 and 1978, in which the President Appointed the Vice President, noting: “Thus gone are the days when a President can appoint a vice President. The two offices are now conjointly elected at the same time by the will of the people at the time of electing the presidential candidate.” The learned Justice cited Section 54(8) of the 1991 Constitution and made it quite clear that the Constitution provides that the removal from office of the Vice President must be by the same means as the removal from office of the President. In his view, “...the removal from office of the Vice President, as stated in the Release from [the President’s] office, is nothing short of an exercise of power that can find no validation in the text of our national Constitution.” The procedure must be in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution. The Applicant’s constitutional rights should have been protected by the Supreme Court. Instead, the Court purported to give efficacy to the violation.

13. The position of the African Commission in Good v Botswana reflects its views in the case of Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights & Associated Newspapers of Zimbabwe v Zimbabwe (2009) AHRLR 235 (ACHPR 2009) [Appendix 22], at paragraph 172. Again, in Purohit and Another v The Gambia (2003) AHRLR 96 (ACHPR 2003) [Appendix 21], at paragraph 72, the African Commission expressed the view that the guarantees in article 7(1) of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights [Appendix 16] extend beyond hearings in the normal context of judicial determinations or proceedings.

14. Within the current context, the President, as well as the APC Party as discussed above, were under a legal obligation to ensure that the allegations which led to the expulsion of the Applicant from the Party and his removal from the Office of Vice-President, were brought before the competent authorities provided for by the national and Party constitutions. Their disregard of those obligations violated the Applicant’s right to the Protection of the Law.

(1.3) Purported replacement of the Applicant done outside provisions of 1991 Constitution

15. The subsequent appointment of Mr. Bockarie Foh as Vice President was purportedly executed in accordance with section 54(5) of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone in a bid by the President to paint his unconstitutional actions with a brush of legality. The section provides that “Whenever the office of the Vice-President is vacant, or the Vice-President dies, resigns, retires or is removed from office, the President shall appoint a person....” It is however submitted that none of the prerequisites which would have allowed for the appointment of Mr. Bockarie Foh were met at the time of the purported appointment.

16. In order that the Vice Presidency be considered as “vacant”, section 55 of the 1991 Constitution provides that (a) the term of office of the President should have expired; or (b) the Vice-President (the Applicant herein) resigns or retires from office or dies; or (c) the Vice-President (the Applicant) is removed from office in accordance with the provisions of section 50 or 51 of the Constitution; or (d) upon the assumption by the Vice-President to the office of President.

17. Sections 50 and 51 of the 1991 Constitution of the Republic of Sierra Leone [Appendix 1] provide that the removal of the President (or the Vice-President, when read in concert with sections 54(8) and/or 55(c)) shall be either upon a determination by a Board appointed by the Head of Medical Services, that the President (or Vice) is physically or mentally unfit; or upon a determination through proper impeachment proceeding in Parliament that there has been a violation by the President (or Vice) of the Constitution for any gross misconduct in the performance of the functions of his office.

18. As is clear from the above, the only means for removing the Vice-President from office are provided by Sections 54 and 55 of the 1991 Constitution. Neither one of those constitutional processes includes a removal by the President suo motu. This, having been established, we are left with the insurmountable conclusion that the Vice-Presidency was not vacant because the term of office of the President was not expired; nor had the Applicant retired, resigned, or died; nor had the Applicant been removed from Office in accordance with sections 54 and 55 (which reference sections 50 or 51) of the Constitution; nor had the Applicant assumed the office of President.

19. How the conclusion was reached that the criteria for establishing the vacancy of the Applicant’s Office had been met, so as to occasion the appointment of a new Vice President, is beyond imagination. The appointment of the purported new Vice President was nothing more than a ploy to impede on the Applicant’s ability to assert his rights as the rightful occupier of the Office. This is a wanton and reckless breach of both the Constitution of Sierra Leone and the right of the Applicant to the protection of that Constitution, and must be instantly rectified by this Court.

(1.4) Refusal of the Supreme Court to allow the amendment of the Applicant’s Case Statement in the face of clear evidence that the amendment was not submitted on time because of circumstances outside of the control of the Applicant

20. The Applicant submits that the Supreme Court, being the constitutional and final court of appeal in Sierra Leone, failed to grant the Applicant the opportunity to fully, exhaustively and impartially present his case to the Court [Appendix 44]. This is in view of the available evidence and the special factual and legal circumstances that the Applicant was faced with against his former Solicitors and Counsel, as well as against the State/Defendants respectively. The Court had on two occasions, by its Order of 15th May 2015 [Appendix 37] and the Order of 1st June 2015 [Appendix 39], ordered the Applicant’s erstwhile Solicitors to serve the Applicant’s Supplemental Affidavit on the Defendants and for both Parties to amend their respective Client’s Case Statements. It was thus strange and unfair that when the Applicant terminated the services of his former Solicitors for failing to do so and appointed new ones who sought to amend the Applicant’s Case in compliance with the Court’s Orders, the Court refused them.

21. The 1st June 2015 Order amending the 15th May 2015 Order [Appendix 39] was to the effect that the Applicant’s Supplemental Affidavit be served on the respective Defendants; and that the Applicant, if he so desired, amends, files and serves his Case Statement on the Court and the Defendants against 4th June, 2015 failing which, the Supplemental Affidavit shall not be used in the proceedings.

22. The correspondences between the Applicant and his erstwhile solicitor [Appendix 40] indicate that the Applicant desired to amend, file, and serve his statement of case. However, his solicitor at the time refused to heed to the wishes of the Applicant, even to the point of filing a Notice to the Court of their intention not to amend the Applicant’s Case. It was for this reason that the Applicant terminated the services of the said solicitor [termination letter and response marked Appendix 41].

23. The Applicant’s new solicitors sought to remedy the damage caused by his former solicitors by a Notice of Motion for an Order to extend time for the Applicant to amend his Case Statement as well as an Order to expunge the Applicant’s Former Solicitors’ Notice to the Court, refusing to amend the Applicant’s Case dated 10th June 2015 [Appendix 42]. This request, however was unjustly determined by the Court [Appendix 44].

24. In the face of the Applicant’s pleas that he had “followed up with [his] erstwhile Solicitors both orally and via cell phone text messages [Appendix 40 herein] to see if they had filed and served the Amended Plaintiff’s Statement of Case per [his] instructions” [emphasis added]; and in spite of the submission of true copies of the letters the Applicant sent out terminating his erstwhile solicitors for not complying with his instructions [Appendix 41 herein, with solicitor’s reply showing no remorse], the Court somehow reached the conclusion on page 4 of its ruling [see Appendix 45] that “The Court gave the Plaintiff an option to amend or not to amend his Statement of Case and by the notice filed on his behalf dated the 4th 2015, he chose the option not to amend.” A grave injustice was perpetuated against the Applicant in the ruling of the Supreme Court, as it substituted for the Applicant’s wishes, the wishes of his former solicitors, creating a very dangerous precedent.

25. When a request was made to remedy the actions of the rogue solicitors, the Supreme Court refused the Applicant’s request to expunge the notice flowing from his erstwhile solicitors that the Applicant did not intend to amend the statement of his case. The Supreme Court’s reason was that the rules which would empower it to expunge the notice, being the High Court Rules 2007, only makes provision for matters which are “scandalous, irrelevant or otherwise oppressive.” [page 9 of Appendix 45] and, in the erroneous opinion of the Supreme Court, there was nothing scandalous or oppressive about the Applicant’s erstwhile solicitors going against his express wishes and representing to the Court, the false notion that the Applicant did not intend to amend his statement of case.

26. The Supreme Court of Sierra Leone’s very own rules of procedure, [Appendix 49] at Rule 93 provide that “A Notice of Motion or statement of the Plaintiff’s case or of the Defendant’s case, as the case may be, may at any time, with the leave of the Court, be amended on such terms as the Court may determine” [Emphasis added]. It is submitted that the terms which the Court determined for the Applicant to amend his statement of Case were that (a) he could do so if he so desired, and that (b) service of the amendment be made on the Defendants by 4th June 2015 [see Appendix 39].

27. The irrefutable evidence in Appendices 40 and 41 indicate that it was the desire of the Applicant that his solicitors file and serve a Supplemental Affidavit in accordance with the 1st June Order. The refusal by the Supreme Court, within the circumstances, to heed the pleas of the Applicant were against the aims of justice and violated his right to Protection and Security of the Law.

(1.5) The wrongful interpretation of the Constitution by the Supreme Court to the effect that the President could remove the Applicant as Vice President in the manner that he did, or at all

28. The Applicant submits that his right to Protection and Security of the Law was infringed when, during the course of the substantive suit, and in determining whether political party participation is limited to the period up to a candidate’s election to office, the Court erroneously reached the conclusion that when read “holistically” with other provisions, section 41 of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone indicated that “political party affiliation of both the President and Vice President is a prerequisite for holding such positions.” [first paragraph, page 19 of Appendix 45]. The relevant portions of the sections of the 1991 Constitution [Appendix 1] relied on by the Court in reaching this conclusion are laid out below:

5(2)(c) the participation of the people in the governance of the State shall be ensured in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution.

35. (1) Subject to the provisions of this section, political parties may be established to participate in shaping the political will of the people, to disseminate information on political ideas, and social and economic programmes of a national character, and to sponsor candidates for Presidential, Parliamentary or Local Government elections. [emphasis added].

41. No person shall be qualified for election as President unless he— b. is a member of a political party; [emphasis added]

29. Clearly, and without a doubt, the Constitution, through section 5(2)(c), makes provision for ensuring participation in governance. Section 41 declares that no person shall be qualified for election as President unless he –b. is a member of a political party. Copious reference has already been made to section 54, where at subsection (2)(a), it is provided that the qualifications of the Vice President are the same as those for the President under section 41. The significance of the political parties to the candidates for the respective positions is reflected in section 35(1) in that “political parties may be established... to sponsor candidates for Presidential, Parliamentary or Local Government elections” [emphasis added]. The role of the political party is therefore as a sponsor; a financial supporter; an entity to vouch for the competence of a candidate. The duties of the sponsor are no longer needed when the candidate is in office; and has the resources of the State; and is performing his duties and functions for the whole world to determine his competence. How then, did the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone come to the conclusion that political party participation is a prerequisite for Presidents and Vice Presidents to continue to hold office?

30. Ironically, the Court cited the Ghanaian case of Agyei Twum v. Attorney-General & Akwetey [2005- 2006] SCGLR 732 at 757, where the learned Dr. Date-Bah, JSC, stated that: “In interpreting constitutional language, one should ordinarily start with a consideration of what appears to be the plain or literal meaning of the provision...That literal meaning needs to be subjected to further scrutiny and analysis to determine whether it is a meaning which makes sense within its context and in relation to the purpose of the provision in question. In other words, the initial superficial meaning may yield to a deeper meaning elicited through a purposive interpretation.” [Emphasis added]. It would seem that the Court glossed over the initial statement made by Dr. Date-Bah and rushed to find a deeper meaning to the text

of the Constitution where one was not needed. A plain reading of the combined provisions makes it abundantly clear that in seeking election as a candidate, affiliation to a political party is a prerequisite as it is necessary, inter-alia, for the political parties to act as sponsors to the candidates seeking elected office. It would seem that the Court was overly excited by Section 5(2)(c) of the 1991 Constitution, which employs the words “participation...in governance.” It would seem that the Court took this provision to mean that all provisions relating to governance must persist throughout an individual’s candidacy as well as his or her term in office, not taking the time to distinguish between provisions made for candidates and provisions made for individuals within their respective offices. Clearly, the provisions cited by the Supreme Court can be for nothing else but candidates. Even the most purposive reading of the provisions indicate as much. This is why Sections 46, 48, 49, 50, 51, 54, and 55 of the 1991 Constitution exist; to regulate what happens and what needs to be maintained once the candidate assumes office. None of these provisions relate to or reference political parties.

31. It is herein submitted that both a literal and a purposive interpretation of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone [Appendix 1] favours the position that membership in a political party is not a continued requirement for the office of President or Vice President. As was argued by learned Counsel for the Applicant during the suit, the reason why the Constitution takes away membership of a political party...as a continued requirement for the office of President and Vice-President upon election is to uphold the sovereign mandate, the sovereignty of the people, so that it is not left in the hands of a political party. It would be mischievous of the Constitution to mandate that the influence of a political party, with its own interests and agenda should prevail over the interests of the nation as a whole. The Government of a country is accountable to all the people, not just to the political party which the President and Vice- President represent.

32. It is accepted that the criteria for eligibility to stand for elected office in the Republic of Sierra Leone requires that the Applicant must have been a member of a political party. That is quite reasonable. When coming into office, it makes sense that a candidate be associated with an organization with recognizable goals and an agenda for the nation. This connection between the candidate and the political party, however, is muted when the candidate is elected into office and becomes not just a representative of the Party, but a representative of all the citizens within the State. In such a position, the individual is no longer exercising a right as a member of a group, but as an individual representing other individuals within and outside of the group to which he belongs. The expulsion of said individual from the group to which he belongs cannot therefore, and must not be allowed to constitute sufficient grounds for his removal from office.

33. The nature of the position held by the Applicant far supersedes the extent of the authority of the Party to which he belonged. Upon being duly elected, his fate was no longer tied to the APC Party, but to the Constitution; and it is the Constitution which can and must be the authority for his removal from office, not the decision of the APC Party or the President of the Republic. The Constitution does not support those modes of removal.

34. The learned Justice Conteh cited the grounds on which the President purported to relieve the Applicant of his position as Vice President [Appendix 14], being that, inter alia, the Applicant was expelled from the All People’s Congress Party. The learned Justice proceeded to educate the President that, “the simple and irrefutable fact is that they do not and cannot in the face of the clear constitutional provisions, provide, with the utmost respect, the warrant or legal basis ‘for relieving with immediate effect’ the Vice President from office.

35. It is unfortunate that the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone deviated so far from the provisions of the 1991 Constitution and has condoned the unconstitutional removal of the Applicant, as well as the unconstitutional occupation of the Applicant’s office which is further impeding the Applicant’s rights.

36. The erroneous conclusion that the Applicant had lost a requirement for maintaining office was touted as a ground on which the Supreme Court leaped to the conclusion that the Applicant could be removed as the Vice President.

37. Amazingly, the said Supreme Court first found and held in its Final Judgment of 9th September 2015 that “the President does not have any power under sections 50 and 51 of the Constitution, nor does he play any direct role in the procedure set out in those sections” on the removal of the Vice President [page 3 at para. 3, lines 4-5 of Appendix 45]!

38. The Supreme Court of Sierra Leone then journeyed outside of the clear provisions and dictates of the 1991 Constitution to create, establish, and enforce a law that did not exist, namely, that the President had power under the 1991 Constitution “to relieve the Vice-President of his Office and duties,” [emphasis added] other than by the procedure set out in sections 50 and 51 of the said Constitution. This unwarranted and unlawful deviation from the clear provisions of the 1991 Constitution (at section 54(3) thereof) in making the Offices of President and Vice-President “selective” positions rather than “elective” entities could be contrasted with section 80(4) of the previous repealed 1978 Constitution of Sierra Leone (Act No. 12 of 1978) [Appendix 47], which made appointments to the then Offices of First and Second Vice Presidents of Sierra Leone entirely selective and discretional to the President of Sierra Leone.

39. In the very similar circumstances of Attorney-General of the Federation & Ors v Alhaji Atiku Abubakara & Ors [Appendix 62], the Supreme Court of Nigeria accepted that the provisions of the Nigerian Constitution do not grant the President or the Supreme Court the power to remove the Vice President from office. The Justices were emphatic and took pains to explain that the provisions of the Constitution were clearly not in favor of the actions taken by the President and that the removal of the Vice President was void and illegal.

40. Contrary to the clear provisions of the 1991 Constitution, the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone indicated that there are no limitations placed in the Constitution as to the methods by which the President or Vice- President could be relieved of his office, and strangely proceeded to extend the powers of the President by declaring him the “supreme executive authority” by virtue of Section 40 of the Constitution, and empowered him to dismiss the Applicant outside the provisions of the Constitution. The Supreme Court also implied that it also had the power to remove the Vice President.

41. Having conjured grounds on which the Applicant could be removed from office, and vested the President with arbitrary power to act as he saw fit, the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone succeeded in certifying the unlawful dismissal of the Applicant and in so doing, violated his right to Protection of the Law.

(2) Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Due Process of Law

42. The Applicant’s right to Due Process of Law was violated in the following Respect:

The Applicant was expelled from the APC Party with immediate effect in flagrant disregard of his right to an Appeal under Article 8(i) of the APC Party’s Constitution and was replaced as Vice President before the time allowed him to appeal against that decision had lapsed.

43. The right to Due Process of Law is recognised under Article 7(1) of the African Charter on Human and People’ Rights [Appendix 16] and Article 14(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) [Appendix 18]. Both the African Charter and the ICCPR have been ratified by Sierra Leone.

44. Due Process of Law encapsulates a fundamental principle of fairness in all legal matters, whether civil or criminal. It demands that all legal procedures set by statute and court practice, must be followed for each individual so that no prejudicial or unequal treatment will result.

45. The Court is referred to paragraph 34 in the case of Civil Liberties Organisation and Others v Nigeria (2001) AHRLR 75 (ACHPR 2001) [Appendix 24], where the Commission observed that “in a [1981 report on the situation of human rights in Nicaragua (oea/serl/v/ii53 doc 25 (30 June 1981))], the Inter- American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) stated that the existence of a higher tribunal necessarily implies a re-examination of the facts presented in the lower court and that the omission of the opportunity for such an appeal deprives defendants of due process.”

46. Article 8(i) of the APC Party Constitution [Appendix 2], allows, ‘every member of the Party aggrieved by a decision of any organs of the Party, with a right of appeal within 30 days of the decision to the immediate higher organs of the Party, in a successive order, up to the National Delegates Conference of the Party whose decision shall be FINAL’. [Emphasis added].

47. The Applicant, however was neither informed of any proceedings relating to his Appeal nor was he called upon to participate in any appeal hearing. [the Party’s Constitution, and said Appeal are marked as Appendices 2 and 7]. In fact, after attending the hearing of the Investigation Committee, the Applicant was never confronted with its findings and recommendations in order to give him the opportunity to challenge same before a decision was made concerning him. No evidence was produced to support the reasons given for his dismissal [see Appendices 3 and 7].

48. Charles F. Margai ESQ, a lawyer of 45 years and the leader of the People's Movement for Democratic Change (PMDC) – the third major political party in Sierra Leone – published a legal opinion dated 20th March, 2015 on the Sacking of the Applicant herein [Appendix 13]. Mr. Margai concluded in part that the expulsion of the Applicant remained open until the expiry of the 30 days allowed for appeal under the APC Party Constitution, subject to confirmation or rejection of the expulsion decision by the National Delegates’ Conference. He added that as the 30 days had not been concluded and there was not a final decision from the National Delegates’ Congress, the President’s decision to sack the Vice-President based on section 41(b) of the 1991 Constitution “was precipitous.”

(3) Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Work

49. The Applicant’s Right to Work was violated in the following 2 Respects:

a. The Applicant was unlawfully removed from his Office as the Vice President of the Republic of Sierra Leone by the President and the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone subsequently denied the Applicant the right to resume his duties in the said Office, without regard to sections 54, 55, 50, and 51 of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone;

b. The actions of the President and the Supreme Court denied the Applicant his right to remuneration, emoluments, social security benefits, and other employment perquisites.

50. The Right to Work is protected under Article 15 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights [Appendix 16], Article 23(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [Appendix 17], and Article 6(1) of The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights [Appendix 19]. The Right to Work captures the simple, but fundamental right of any human being to work and engage in productive employment without undue interference. Productive employment leads to earnings, which in turn allows an individual to cater for physiological needs, provide for his or her family, maintain a certain level of comfort in life, and have a sense of fulfilment in life.

(3.1) The unlawful removal of the Applicant from his Office by the President and denial by the Supreme Court for the Applicant to resume same.

51. The Applicant submits that the actions of the President in unlawfully removing him from his office as Vice President are tantamount to the wrongful termination of his employment. The law which governs the Applicant’s Office as Vice President is the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone [Appendix 1] chiefly, Sections 54 and 55, both of which refer to sections 50 and 51 as the procedure by which the Applicant may be removed from office.

52.This Court is referred to the case of Folami v Community Parliament (2008), SUIT NO: ECW/CCJ/APP/01/07; JUDGMENT NO. ECW/CCJ/6/10/08 [Appendix 48], wherein learned Counsel to the Applicants, at page 9, referred to the case of Gateway Bank v Abodose (2003) 1 WKN 138-147 ratio 1, and the statement of the Court that the employee has the onus to place before the Court the terms of the contract of employment, and to prove in what manner the said terms of the contract were breached by the employer.

53. The Applicant has submitted above that the terms of his contract of service are to be found in the 1991 Constitution and that specifically at Sections 50 and 51, the grounds and procedure by which the Applicant is to be removed from office are laid out clearly for the world to see. If it is accepted that a deviation from those provisions constitute a breach of the terms of the Applicant’s employment, then it must be accepted that in circumventing the Constitution, the President breached the terms which kept the Applicant in Office.

54. It must not escape the notice of this Court that the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone found and held in its Final Judgment of 9th September 2015 that “the President does not have any power under sections 50 and 51 of the Constitution, nor does he play any direct role in the procedure set out in those sections” [page 3 at para. 3, lines 4-5 of Appendix 45]. It is unfortunate that the Supreme Court then leaped outside of the clear provisions and dictates of the 1991 Constitution to hold further that the President had power under the 1991 Constitution “to relieve the Vice-President of his Office and duties,” other than by the procedure set out in sections 50 and 51 of the said Constitution. In so doing the Supreme Court abandoned the Constitution, and condoned the violation of the rights guaranteed the Applicant under Article 15 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights [Appendix 16], Article 23(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [Appendix 17], and Article 6(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights [Appendix 19].

55. The Constitution, as the employment contract which governed the Office of the applicant, makes provision for termination of the Applicant’s employment upon the presentation of valid reasons and within a forum which allows the Applicant to defend himself against the allegations which have been made against him, and which the President and the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone purported to use as a basis to dismiss the Applicant.

56. This Court is further referred to paragraph 6 of the judgment in Moatswi and Another v Fencing Centre (Pty) Ltd (2004) AHRLR 131 (BwIC 2002) [Appendix 25], where the African Court of human rights stated that, “The employment of a worker shall not be terminated unless there is a valid reason for such termination connected with the capacity or conduct of the worker, or based on the operational requirements of the employer. (See article 4 of the Termination of Employment Convention, ILO Convention 158 of 1982.) Before the employment of a worker is terminated for reasons related to her conduct or performance, she must be provided with an opportunity to defend herself against allegations made.” [Emphasis added]. As has been submitted above, there is a noticeable lack of valid and substantive reasons for the termination of the Applicant. What makes matters worse is that the Applicant was also denied the opportunity to defend himself against the unsubstantiated allegations because he was removed without regard to the process and procedure provided under the 1991 Constitution.

57. The Applicant submits that it was in view of the Constitutional provisions that the learned Justice Abdulai Conteh wrote in his open letter to the President that, “reliance on the expulsion of the Vice President from the APC as a warrant for his removal from office can find no justification in the textual provisions of the Constitution.” and later that, “...the removal from office of the Vice President, as stated in the Release from [the President’s] office, is nothing short of an exercise of power that can find no validation in the text of our national Constitution.” [Appendix 14].

(3.2) Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Remuneration, Emoluments and Benefits of Employment

58. It is submitted that as Vice President of the Republic of Sierra Leone, the Applicant is a Government official and an employee of the State. As such, he is guaranteed the protection of the fundamental human right to work, which was infringed upon by his unlawful and unjustified purported removal and replacement as Vice President of the Republic. His employment as Vice-President provides him with adequate earnings, and is the means by which the Applicant provides for himself and his family; it allows him to live a healthy life and he, prior to his unlawful removal, had no anxieties about being able to hold himself out as an able man.

59. The Applicant submits that by virtue of his occupation of the office of Vice President, he had a salary and perquisites, all of which the Applicant has been deprived since his unlawful removal from office on 17th March 2015.

60. A necessary feature of all good employment is the retirement benefits which are derived from social security payments made during the pendency of the individual’s employment or end of service benefits. By illegally removing the Applicant from his office, the Defendant have stripped the Applicant of this very necessary assurance which all employees look to as a safety-net; a hamper of financial security when they are no longer able to work.

(4) Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Participate in Government

61. The Applicant states that his right to participate in Government has been violated by the Defendant. The Applicant submits that through arduous and risky enterprise; commitment to the APC Party and its agenda for the nation of Sierra Leone; and a genuine urge to be of service to his fellow countrymen, he supported the APC Party. The Applicant stood side by side with the President, who has now turned against him, and braved the sometimes treacherous terrain of Sierra Leonean politics in order to participate in government at the privileged level of Vice President. The Applicant’s Right to Participate in Government is captured under Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights [Appendix 18]; Article 13 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights [Appendix 16]; and Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [Appendix 17].

62. The Applicant submits that he has done everything in his power and in the interest of his nation to serve as a diligent and unifying Vice-President and that his Right to Participate in Government was violated by his unlawful removal from Office by the President, and the subsequent denial by the Supreme Court of the Applicant’s attempt to lawfully resume his position as Vice-President, without regard to sections 54, 55, 50 and 51 of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone.

63. This Court is humbly referred to Mouvement Ivoirien des Droits Humains (MIDH) v. Côte d’Ivoire (2008) AHRLR 75 (ACHPR 2008) [Appendix 26]. Though the case revolved around political participation in the sense of restrictions on the right to stand for elective office, and the Applicant’s case turns on his right to maintain his elected office, the words of the African Commission are of some relevance to the Applicant’s case. At paragraph 82, the Commission recognised the right of each State to adopt regulations and criteria to assume elected office. The Commission noted however, that these criteria must be reasonable, objective and justifiable. They must not seek to take away the already accrued rights of the individual.” (emphasis added). At paragraph 83 the Commission further stated, “The African Commission is of the view that the right to vote as well as the right to stand for election are rights attributable and exercised by the individual.... the exercise of the right to stand for elections is a personal and individual right which must not be tied to the status of some other individual or group of individuals. The right must be exercised by the individual simply because he/she is an individual, and not tied to the status of another individual. Distinctions must thus be made between the rights an individual can exercise on his own and the rights he/she can exercise as a member of a group or community.” (emphasis added).

64. Clearly, from the arguments and case cited above, the Applicant’s personal right to participate in government and governance has been effectively curtailed by the Defendants.

(5) Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Personal Safety and Security

65. The Applicant’s Right to Personal Safety and Security was violated in the following Respect:

a. On 14th March 2015, the Applicant’s home was surrounded by soldiers who were not part of his regular security detail and the Applicant’s personal security were relieved of their weapons by the soldiers. All this was done without previous notice to the Applicant, on the orders of some official of the Sierra Leone Government.

66. The Right to Personal Safety and Security is protected under Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [Appendix 17]; Article 6 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights [Appendix 16]; and Article 9(1) of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights [Appendix 18] and by its actions, the Defendant is in breach of its responsibility to ensure the personal safety and security of the Applicant.

67. On 14 March 2015, News media reported that the Applicant sought asylum at the United States Embassy following the surrounding of his house by soldiers [Appendix 4]. It was further accurately reported that the Applicant told the Associated Press he no longer felt safe in the country. He stated that he had been informed by top officials in the Presidential guard that the soldiers were acting on orders from the President [Appendix 5]. The soldiers who surrounded the Applicant’s home, upon arriving there, disarmed all thirty-eight (38) of his personal guards, leaving behind five (5) armed and unknown men. One paper reported that witnesses described heavily armed men entering the home of the Applicant while he was away, disarming his guards, and leaving with bundles of files [Appendix 4]. The soldiers gave no warning of their arrival to the Applicant, and though the Government claimed the soldiers were there to rotate the Applicant’s security, the circumstances do not reflect that position. What is quite evident, however, is that the Applicant was made to fear for his life.

68. In disarming and removing the Applicant’s guards, the soldiers relieved them of the tools which would otherwise be applied in the protection of the Applicant. In so doing, they unduly and unjustly deprived the Applicant of his means of security; they left him open to attack, ambush, and harm to his person and his family, all while the President and his subordinates painted a picture of the Applicant as unpatriotic and a threat to the security of the State. Doing this to a high risk individual such as a Vice President is equivalent to sentencing him and his family to harm and to death.

69. The Court is humbly referred to Oló Bahamonde v Equatorial Guinea (2001) AHRLR 21 (HRC 1993) [Appendix 27]. The complainant claimed that he was subjected to harassment, intimidation and threats by prominent politicians and their respective services on a number of occasions. At paragraph 9.1, the Human Rights Committee observed that, “The first sentence of article 9(1) [of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights] guarantees to everyone the right to liberty and security of person.” The Committee further noted that the right to security, “may be invoked not only in the context of arrest and detention...”.

70. The Court is also referred to the case of William Eduardo Delgado Páez v. Colombia, Communication No. 195/1985, U. N. Doc. CCPR/C/39/D/195/1985 (1990) [Appendix 28]. At paragraph 5.5 the Human Rights Committee stated as follows: “The first sentence of article 9 [of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights] does not stand as a separate paragraph. Its location as a part of paragraph one could lead to the view that the right to security arises only in the context of arrest and detention. The travaux préparatoires indicate that the discussions of the first sentence did indeed focus on matters dealt with in the other provisions of article 9. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in article 3, refers to the right to life, the right to liberty and the right to security of the person. These elements have been dealt with in separate clauses in the Covenant. Although in the Covenant the only reference to the right of security of person is to be found in article 9, there is no evidence that it was intended to narrow the concept of the right to security only to situations of formal deprivation of liberty. At the same time, State parties have undertaken to guarantee the rights enshrined in the Covenant. It cannot be the case that, as a matter of law, States can ignore known threats to the life of persons under their jurisdiction, just because that he or she is not arrested or otherwise detained...” (Emphasis added). This position was cited and applied to hold Zambia in breach of its responsibility to ensure the personal security of the complainant in Chongwe v Zambia (2001) AHRLR 42 (HRC 2000) [Appendix 29] at paragraph 5.3.

71. The position of Vice President of any nation is one fraught with danger. Assumption to that office carries the threat of assassination, intimidation from assailants both at home and from abroad, the publication of one’s private affairs, including where the Vice-President lives, where he eats, places he visits, and so on. Disrupting his security detail in that manner amounts to putting his life and that of his family, friends and associates in imminent peril.

72. It is the duty of the State, as emphasized in the judgment of the Court in William Eduardo Delgado Páez v. Columbia, to ensure the safety and security of its citizens. The level of the duty owed is increased exponentially when regarding an individual, such as the Applicant, who faces threats to his life and person because of the commitment he has taken to serve his nation.

73. It is submitted that the actions taken by the soldiers at the home of the Applicant were intimidating and threatening. Further, disarming the Applicant’s guards at a time when the Applicant had been unjustly accused of seeking to incite violence left him exposed to harm, and therefore these actions were an infringement of the personal safety and security of the Applicant, contrary to Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [Appendix 17], Article 6 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights [Appendix 16] , and Article 9(1) of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights [Appendix 18].

74. Rather than taking the appropriate and necessary steps to ensure that the Applicant was safe and secure, the Defendant rather proceeded to take actions which put the Applicant in jeopardy and infringed on his right to personal safety and security.

(6) Violation of the Applicant’s Right to Dignity

75. The Applicant’s Right to Dignity was violated in the following two (2) Respects:

a. The President caused to be issued, a press release in which he accused the Applicant, inter alia, of exhibiting a willingness to abandon his duties as Vice President. This was also done without regard to the Applicant’s good name and reputation;

b. The disruption of the Applicant’s right to work leading to insecure finances and limited ability to live a life of dignity.

76. The Right to Dignity is protected under Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights [Appendix 18], Article 5 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights [Appendix 16] and Article 1 of Universal Declaration of Human Rights [Appendix 17].

(6.1) Unsubstantiated Allegations Against the Character of the Applicant

77. It is humbly submitted before this Court that defamatory statements and other statements of a nature which – as his Lordship Baron Parke put it in the English case of Parmiter v Couplands (1840) 6 M & W 105 [Appendix 30] at 108, expose a person to hatred, ridicule or contempt; or as was the opinion of the court in Youssoupuff v M.G.M Pictures [1934] 50 T.L.R. 581 [Appendix 31], tends to hinder mankind from associating or having intercourse with him; or, in the view of Lord Atkins in Sim v Stretch [1936] 2 ALL ER 1237 [Appendix 32], “...tend to lower the plaintiff in the estimation of the right-thinking members of the society generally”, – infringe on a person’s right to dignity.

78. The dignity of a person is reduced by subjecting that person to the kind of unlawful and unwarranted humiliation which is the result of malicious defamation. It is for this reason that Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights [Appendix 18], makes specific provision against “unlawful attacks” on “honor and reputation.”

79. In his Press Release announcing the purported removal of the Applicant from the office of Vice President [Appendix 6], the President announced that he had “taken note” of the decision to dismiss the Applicant from the APC Party, which is inclusive of the grounds on which he was removed, that is, “behavior amounting to fraud, inciting hate, threatening personal security of key Party Officials, carrying out anti- party propaganda and engaging in activities inconsistent with the Party’s Objectives.” [See Appendix 3]. In the same Press release the President also stated that the Applicant had demonstrated “a willingness to abandon his duties and office as the Vice President...”

80. As at 15th March 2015, the allegations of orchestrating political violence and forming a new political party had made their way to reports in The Guardian Newspaper [Appendix 5], an internationally circulated paper. The publication has carried the false allegations against the Applicant far and wide into the public domain, expanding the damage being caused to the Applicant’s name and reputation.

81. The Applicant humbly refers this court to the case of Purohit and Another v The Gambia (2003) AHRLR 96 (ACHPR 2003) [Appendix 21]. Though the case involved the mentally challenged and revolved around, inter alia, issues of equality, non-discrimination, and cruel, inhuman/degrading treatment, the Court stated at paragraph 58 line 4, with much relevance to the current case, that “Personal suffering and indignity can take many forms, and will depend on the particular circumstances of each communication brought before the African Commission.” The Commission had observed at paragraph 59 that persons with mental illness had been “branded as ‘lunatics’ and ‘idiots’, terms which without any doubt dehumanise and deny them any form of dignity in contravention of article 5 of the African Charter.”

82. It is herein humbly submitted that the Commission in Purohit and Another v The Gambia (2003) AHRLR 96 (ACHPR 2003) took into consideration the nature of the persons against whom the statements had been made, the effect on them, and the image the words would portray of them. The same formula is being asked of this Court. The Applicant is a politician within a nation which has had more than its fair share of hateful political rhetoric, divisiveness, and political upheaval and destabilization – which includes the ten-year civil war the country experienced between 1991 and 2001 – resulting from people in the position of the Applicant doing exactly what the Applicant has been falsely accused of doing, that is, inciting hate, threatening the personal security of key Party Officials, carrying out anti-party propaganda [see Appendix 3], fermenting trouble and violence in his home district, lying about his faith/religion, and forming a separate Political Party [see Appendix 7], amongst the many other accusations.

83. The social outrage against the Applicant, the perception of him as an immoral man and the embarrassment which is the inevitable result from his wrongful dismissal, not only affect the Applicant’s good name and character, but have also contributed to severe emotional and psychological trauma. Such infringements of the Applicant’s right to dignity as have been perpetrated were bound to have unfortunate effects on his psyche.

84. In light of the position of the Applicant and considering the history of the nation in which he holds such position, the declarations and accusations laid against the Applicant without justification amount to a malicious and unlawful attack on his honor and reputation, contrary to Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights [Appendix 18]; it lowers the estimation of the Applicant within the eyes of reasonable members in society, causes him to be ridiculed, hated and shunned by those who unfortunately believe the accusations, and as such, infringe on his right to dignity, in contravention of Article 5 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights [Appendix 16] and Article 1 of Universal Declaration of Human Rights [Appendix 17].

(6.2) Disruption of the Applicant’s Right to Work leading to destabilized finances and hampering his ability to live a life of dignity

85. The unconstitutional removal of the Applicant as Vice-President unjustly deprived him of the benefits of gainful employment, opening the door to anxiety over finances, embarrassment, and the possibility of not being able to cater for himself and his family, thereby infringing on his right to health; both physical and mental. The applicant is unfortunately afflicted with the stigma and infamy of a very public dismissal, unjustly executed to deprive him of the rights and benefits accorded by his employment.

86. In Mohammed EL-Tyyib Bah vs. Republic of Sierra Leone (Judgment of 4th May, 2015) Suit No. ECW/CCJ/APP/20/13; Judgment No. ECW/CCJ/JUD/11/15 [Appendix 46], this Court recognized the effects of an unjustified deprivation of the right to work on an individual at page 17, observing that “...the Applicant in this case, has suffered pain, mental, psychological trauma and deprivation. Indeed, as expected, dismissal carries with it some measure of infamy and stigma and deprives the individual the right or benefits accorded by the employment and society at large.”

87. The Applicant requests that this Court takes special notice of the way in which persons who are without gainful employment are viewed within the African context. Worse off are those who are forcibly removed from their offices on allegations such as those which have been falsely laid on the head of the Applicant. The damage which is continuously being done to the Applicant is immeasurable.

SUMMARY OF PLEAS IN LAW:

A. It is submitted in totality that the intervention of the ECOWAS Court is crucial to addressing and providing adequate redress to the many violations of the Applicant’s Rights as follows:

i. The violation of the Applicant’s Right to Protection and Security of Law under Article 3(2) of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and as enshrined in sections 15(a), 23(2) and 28 jointly and/or respectively of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone, which was infringed upon and violated by the Defendant through the President, and the woefully unfair treatment of the Supreme Court in its proceedings as well as its misapplication of the law.

ii. The expulsion of the Applicant by the Party without a right of appeal, as provided him under the 1995 APC Constitution, violated his Right to Due Process of the Law under Article 7(1) of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and Article 14(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

iii. The illegal removal of the Applicant from his office as the Vice President unduly and unjustly deprived the Applicant of his livelihood, remuneration, and emoluments; and violated his Right to Work, contrary to Article 15 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Article 23(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and Article 6(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

iv. The unconstitutional and baseless removal of the Applicant from the office of Vice President amounts to a denial of the Applicant’s Right to Participate in Government and violated this right as enshrined in Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 13 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

v. Dispatching soldiers to the Applicant’s home and disarming his guards at a time when the Applicant was at great risk and exposure, considering his position as Vice-President and taking into consideration the allegations surrounding him at the time, violated the Applicant’s Right to Personal Safety and Security contrary to Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Article 6 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights; and Article 9(1) of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights.

vi. The false declarations and accusations made against the Applicant without justification, and the termination of his benefits from employment, amount to an unlawful attack on his honor and reputation, in violation of his Right to Dignity as guaranteed under Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; Article 5 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

B. The intervention of the ECOWAS Court is also necessary to address a yawning and imminent constitutional crises created by the bad precedent set by the actions of the Defendant. This Court is asked to consider what would occur should the party expel the President, or both the President and Vice President at the same time, as members and insist that they are no longer President and Vice President by virtue of that expulsion. The Party could also continue expelling subsequent Presidents and vice Presidents at its whim. It is unimaginable, the magnitude of chaos which could arise and spread across Sierra Leone and the sub-Saharan region should this poisonous precedent be allowed to stand. In clear violation of constitutional and fundamental human rights, a precedent could be set which would be catastrophic not only for the Republic of Sierra Leone, but for any other nation which comes to face a similar situation.